“What the hell is water?”

The Edge of 30 Degrees

Yin Yue Dance Company eröffnet in Aachen das schrit_tmacher Festival

By: Ilona Roesli

„…The Edge of 30 Degrees dips a toe in uncharted waters…“

In a commencement speech over a decade ago, one of my favourite writers, David Foster Wallace, started his talk by sharing a parable about two young fish:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says:

“Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes:

“What the hell is water?”

He goes on, while excusing himself for coming across a bit moralistic, to explore a way of thinking that has become the default for many of us. We think that most events befall us: especially events concerning the dreadfulness of doing groceries or the poignancy of public transportation. We make everything about us (why is the cashier being so unfriendly to me? – why does my coffee mug fall into my lap? why does the person who smells the most in this train picks the seat beside mine?). We have absolutely no attention for the presence of other existing human beings or things. And we have no idea what the hell water is.

And I won’t go on some sort of elucidation in defending the arts – that narrative has transformed itself into a tiresome been-there-done-that-situation. The role of the arts in the dreadfulness of life. Or on choosing to frame it differently, and the role of the arts in that process. I really won’t. So I will leave this to be the end of an unfinished thought and an ongoing string of associations related to Wallace’s fish parable.

Here is the catch: I have to credit these thoughts to a performance I saw.

In an empty theatre, that normally functions as a steel factory, I sit and wait while my two colleagues are setting up their cameras. I feel bad for being so easily prepared for my job, carrying a pen and a notebook in my little canvas bag. I start to take photographs of this empty, but fully prepared stage setting, but quickly remember the shitty camera of my phone. I had been there the day before, in broad daylight, with the performers rehearsing and for an interview with choreographer Yin Yue. Now, standing here, there’s nothing like the feeling of being in a space that soon will be crowded by audience, performers, staff and technicians. But beating them to it without having to do any work just yet feels even more voyeuristic than actually attending the rehearsals.

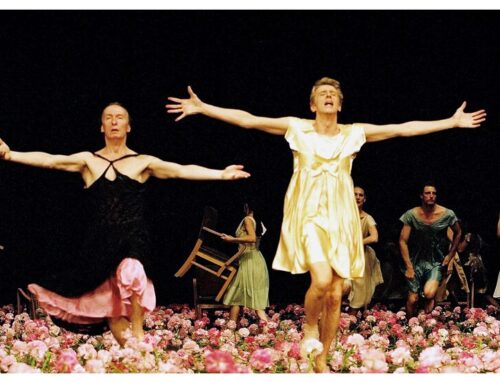

YY Dance Company The Edge of 30 Degrees

Still an hour left until the performance. This is the point that choreographers, directors, actors and many other artists tell themselves or are told: you have one hour left. It is merely one of the time-related themes that Yin Yue incorporates in her new work The Edge of 30 Degrees. Yue, who works with FoCo Technique in her choreographic practice, interprets time in the structure of interactions rather than the linear forms we know. According to French philosopher Henri Bergson, the way we structure time now is according to events that stand out. He goes on proposing that every event in our life must be reunited in order to represent time that is continuous. Duration is change. Its importance is not decided according to absolute numbers (something that can considered to be a moment can have as much weight as a relationship of years according to this theory, although most of us would probably not see it that way). If time is structured, not in absolute numbers of seconds, minutes or hours, but in interactions, what sort of movements would arise to the surface?

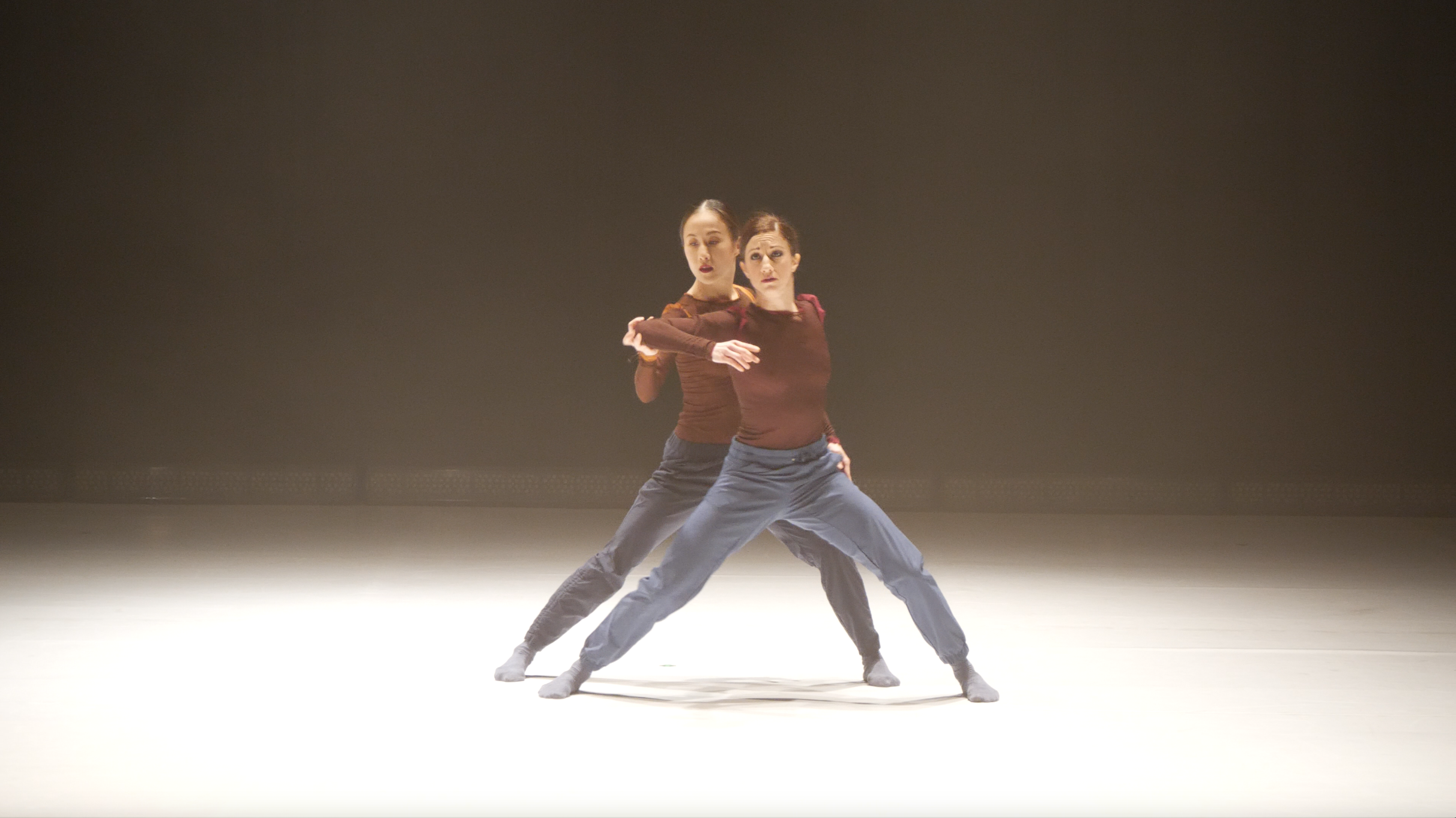

YY Dance Company The Edge of 30 Degrees

In Yin Yue’s The Edge of 30 Degrees, which had its world premier in Aachen, every possible individual movement that could continue into another movement, is interrupted by a movement from another performer. Every movement is punctuated by a new one. Straight lines are out of the question. In the first part of the work, a duet between Yin Yue and Grace Whitworth reflects a relationship that is neither based on oppositions nor on similarities, but rather a sequence of movements that instigate another. This idea of causality seems to suggest that any movement is a reaction or a consequence of another, so that every interaction between performers or movements have the same weight. In Bergsonian sense, Yue’s The Edge of 30 Degrees has some of that same non-hierarchical emphasis on time.

We live with the idea that we are left with only minutes or hours until the next. Yin Yue’s practice reflects, but also deconstructs this rooted idea. The idea of movement, consisting out of space and time, is extended with a human dimension of interaction. And so, The Edge of 30 Degrees dips a toe in uncharted waters.

YY Dance Company The Edge of 30 Degrees