schrit_tmacher festival 2024 – second week

Until we sleep

Far From the Norm and Botis Seva at Kerkrade Theatre

By Thomas Linden

When a grenade hits, you can hear the sound of the chunks of earth falling to the ground after the detonation. After the deafening bang, it sounds like a gentle rain. The audience in Kerkrade received plenty of samples of this acoustic impression during the performance of Botis Seva’s production „Until we sleep“. Again and again, the thunderclaps rumbled through the dark theatre hall. The London-born choreographer and his black dance troupe Far From the Norm position themselves with post-colonial themes. At times, his production felt like a declaration of war on the white audience. The ensemble’s decision not to accept the audience’s ovation after the final chord was in keeping with this. This creates the impression of a self-contained performance that presents its statement and, like an erratic work of art, no longer needs to be appreciated in individual theatrical performances.

Botis Seva is known for his multimedia approach to the possibilities of the stage. He often works with photography, film, projections and installative backdrops. „Until we sleep“ renounces all pop-cultural references and restricts itself all the more effectively to the possibilities of light alone, and even this is used only sparingly. Light rods appear in a semicircle, tapering like polished lances. Light mostly comes from above, only through a centred spotlight, as if there were a gap up there into which the brightness from outside would penetrate. The seven-member ensemble seems to be in a kind of primeval cave, enclosed in a darkness that refuses to go away and doesn’t actually break open until the very end. Hope is not the order of the day in a world that has been characterised by oppression for centuries. It is fitting that the production knows almost no colours. Apart from the bloody red in which the spears of light are bathed for a few moments, there is only a sandy, dull light reminiscent of the late afternoon sun of the savannah.

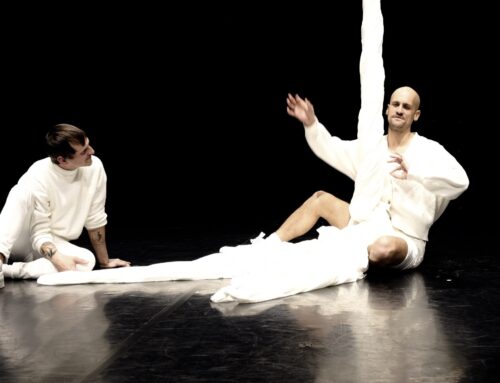

It seems obvious that you are in Africa, as the costumes – somewhere between furs and shaggy woollen creations – correspond with elements of African tribal dances. The ensemble either dances in circular formations or moves across the stage as a horde at breakneck speed. Faces are not recognisable, the bodies appear as anonymous creatures in motion. Subtly turned away, they ignore the audience’s gaze. What is happening here seems to take place behind the fourth wall of the stage. All movement remains focussed on the light and the imaginary gaze of a deity who is in an outside world that can only be guessed at.

Botis Seva builds a kind of bridge between an Africa of archaic darkness and the streets of an angry 21st century. Although the Englishman is regarded as one of the kings of hip-hop, his use of its dance elements here is very restrained. The key to this choreography lies in krumping, the sub-form of hip-hop that began to develop in Los Angeles after the turn of the millennium. It is sometimes compared to a danced prayer. The dancers are completely focussed on themselves. Botis Seva demonstrates this meditative element, which is nevertheless charged with enormous energy, in great detail. People stomp, step and jump in a circle. Then these tableaux are broken up by a swift race in the darkness, or sudden leaps are followed by dancers spinning in the air. Fast, expressive and with an impressively aggressive dynamic potential, a trance-like situation of worship is created. It is broken up towards the end by a hunter who fires his weapon in the centre of the room. He too is a black figure. There is no colonial setting of black and white on stage here. Botis Seva does not act out any stereotypes. The hunter aims into the audience and pulls the trigger, the whipping shots cannot be overheard.