The spectator gets no absolution…

Sinful light

Premiere of the Polish Dance Theatre and „Bodytalk“ with „24/7 New Sins“ in Poznan marks their fourth successful collaboration

review by Barbara Kowalewska (Kultura u Podstaw portal)

On 23 April 2024, the stage of the Polish Dance Theatre became for a moment a „theatrical pulpit“ from which the sins of the modern world were pointed out. And the spectator gets no absolution.

This is another – as part of the jubilee celebrations – premiere of the Polish Dance Theatre, this time fitting in with the theme of this year’s idiom: „Man – object“ and the discourse on the objectification of man today. The title of the performance, 24/7 New Sins (choreography and direction: Yoshiko Waki, dramaturgy: Rolf Baumgart), on the one hand evokes associations with the catechism of the Catholic Church, and on the other refers to the abbreviation ’24/7′, commonly used in business today to mean that a service is provided without interruption. The term also appears in the title of Jonathan Crary’s book: „24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep“, in which the author criticises the modern economic system, which seeks to appropriate our time, including taking away the right to sleep „and eliminating the useless minutes devoted to reflection and contemplation“. What ’24/7′ and what new sins did the creators of the premiere show want to tell us about?

Controlled bodies

The dancers appear on stage in their natural but exaggerated role. Recording themselves with mobile phones, they advertise themselves as exemplary ‚dancefluencers‘ or ‚infludancers‘ (‚we look good, we control our bodies‘). This obvious play on words alluding to today’s influencers may seem like a boring repetition of warnings against compulsive social media immersion and the marketisation of bodies. However, one should not conclude from the fact that something is common knowledge that it is no longer worthy of discussion. Habit weakens vigilance and inhibits the impulse to take action. If we are not yet concerned enough, it is worth recalling that a report by the Inspiring Girls Poland Foundation, which investigated the career aspirations of girls in our country, yielded worrying results: around 46 per cent of them want to become a youtuber, instagrammer or tiktoker in the future (supported by 12 per cent of their mothers). Against this backdrop, a scenic take on what would seem to be a tired topic becomes a pressing need.

The object as a source of emotion

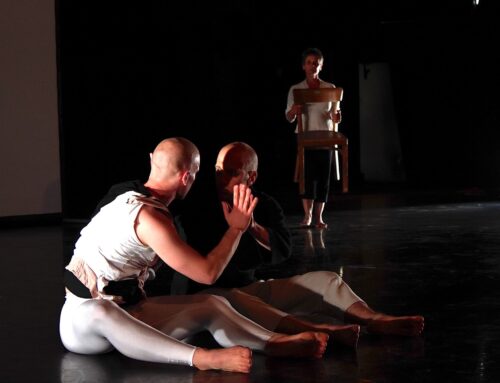

The contemporary fetish, the smartphone, an object of desire and one of the symbols of late capitalism, without which many cannot imagine happiness, does not, however, make it possible to achieve this state, because, as Zygmunt Bauman wrote, ‚the market feeds on the sense of unhappiness it generates itself‘. While in everyday life mobile phones are often tools that theatricalise personal life, in the play it is the other way around – mobiles turn into theatrical props. Based on social media activity, one can see the constant and unmet need for attention, leading to emotional states that are exaggerated in the performance: on stage, we are confronted with the physical expression of extreme affects, bodily agitation, tiring emotional undermining, which continues to grow despite the violent discharges. Screaming, thrashing, fighting, all in a kind of drunken stupor, dazed and at maximum intensity. It is not a pleasant picture, yet it seems that the viewer has been subjected to this tormenting discomfort on purpose.

A post-narrative world

It is difficult to speak of any kind of logical, in the traditional sense, narrative here. The show is stitched together from scraps of story like memes or posts – everything here is temporary. The props (Hagen Keller), clumsily cut out of sponge, emphasise the ugliness, impermanence and shoddiness inherent in many creations of the internet, including the now idealised artificial intelligence. It is worth recalling that ’24/7 New Sins‘ is the fourth co-production of the Polish Dance Theatre with the Bodytalk artistic collective, which creates in the so-called Brutalist aesthetic, which is reflected not only in the expression of movement, but also in the scenography: props are treated as junk, temporarily only useful objects. At one point in the performance, a huge sack of clippings of the spongy material from which they are made is scattered by the dancers; the sponge fragments choke the viewer with their excess and, at the same time, their superfluousness. In a world of this superfluity and artificiality, the story that gives life some meaning and purpose is missing. Human bodies (those that the dancers smilingly referred to as ‚controlled‘ at the beginning of the performance) mingle with these offcuts, die in convulsions, lost in anonymity, devoid of human dimension. That’s how mortal sinners die, but it’s also how something else dies – the world we knew, which seemed to be planted on some kind of sensible foundation.

There is no light at the end of the tunnel

In reaction to such a dystopian image one wants to protest: after all, this is not the only truth about our reality! The audience may feel a revolt – where is there any hope in all this? Not in Vivaldi’s music, drowned out by disturbing electronics, nor in the rachitic plant, which looks grotesque in a jumble of artificial creations and exists only for a moment. Brutalism takes over the stage. But perhaps this is the effect the filmmakers wanted to achieve – the hunger for something human is stronger the more dehumanising, horrific the image becomes. The most poignant moment is the final effect built by means of a light projection (Sven Stratmann), creating the illusion of tunnel or corridor architecture. This optical illusion – which evokes a strong feeling of claustrophobia, sucking the viewer into the digital machine – reminded me of the particular architecture of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, which made a similar and equally strong impression on me. The games of light that conclude the performance are not the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel, but beams of radiation coming from the screens of electronic devices that permeate us, confine us, overwhelm us and suffocate us. The performance leaves us without answers as to how to deal with this – rather, it calls us to wake up and ask questions about the future of what is human in the face of the blind admiration of digital technology and artificial intelligence developing in an unknown direction.

Polish Dance Theatre and Bodytalk: „24/7 New Sins“, choreography and direction: Yoshiko Waki, dramaturgy: Rolf Baumgart, music: Patryk Pilasiewicz and collage and adaptation: Antonio Vivaldi, Steve Reich, Andrzej Konieczny, Melanie Martinez, costumes and set design: Nanako Oizumi, lighting design: Timo von der Horst